The Sound

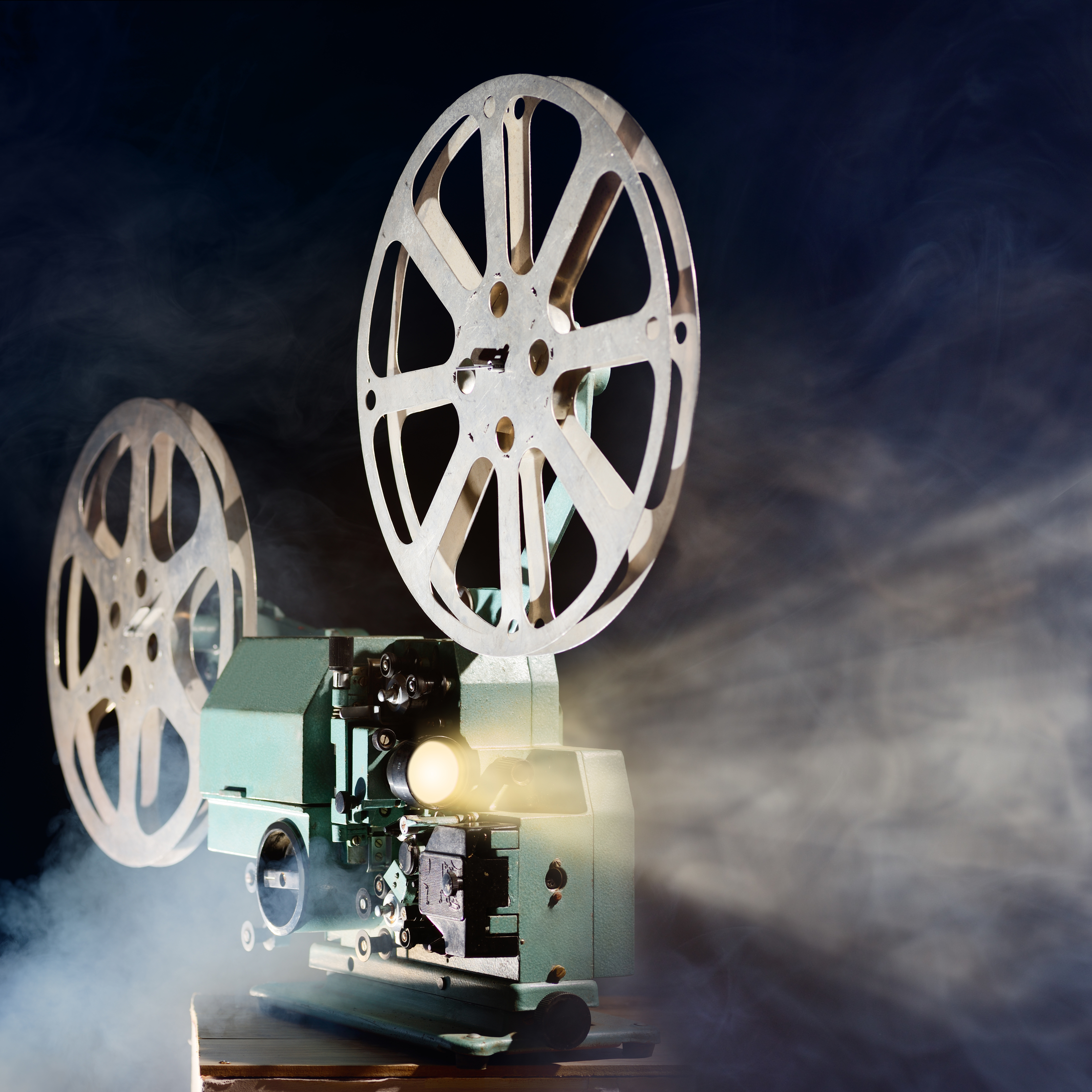

He is sitting in the dark, talking to a friend. The friend, a woman, is hidden in shadow, hinted at only by the flickering light pouring from the movie projector. The projector is making a rhythmic clicking noise, not unlike the one he is talking about as he points to the screen.

“Ruined a perfectly good Mickey Mantle baseball card,” he says to the friend. Her name is Miranda. “Would have been worth a ton today if I’d kept it in a plastic sleeve in a box in a safe in a closet in a well-guarded house,” he says, the smile obvious in the sweetness of his sibilance.

He concentrates on the clickety-clickety of the projector, watches the skinny, inkling of a boy ride his bicycle down an empty street.

This isn’t the sound he hates most.

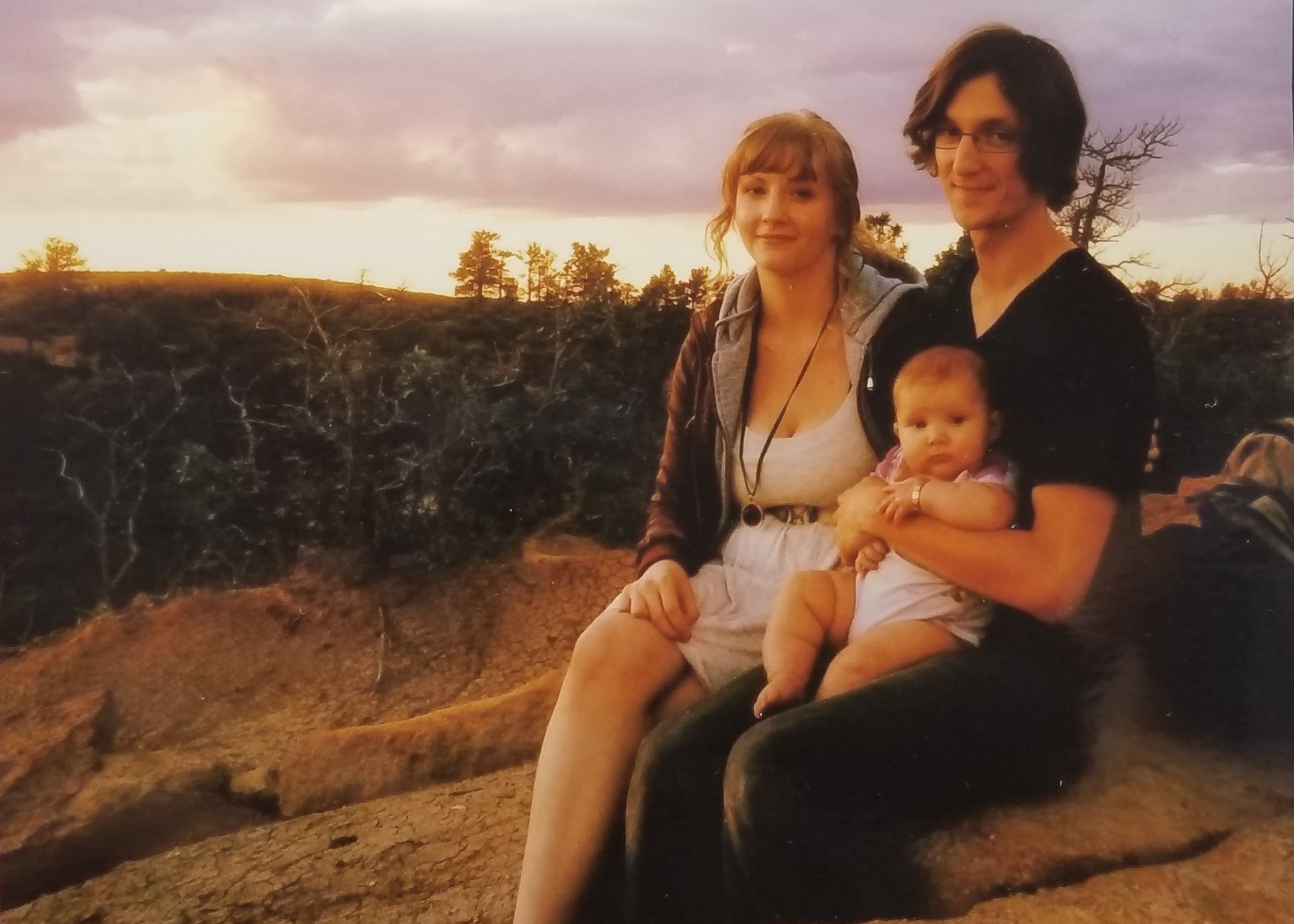

“I love this next part,” he says, pointing. His hand breaches the spray of light and draws a temporal shadow puppet on the screen. The faded image flickers and hiccups across a splice, changing from a sunny afternoon to murky twilight. Three children – himself, his best friend Ray, and…he can’t recall the girl’s name but he thinks of her as Pamela – are chasing fireflies down the street, rows of tall oak trees on either side framing their small, running bodies like a scene out of a Spielberg movie. He is seven. No…eight.

“There were dozens of them,” he says, “maybe hundreds. But the movie camera didn’t capture them.” He coughs, takes a deep breath, exhales. “Except there! Right there. Did you see it? The lightning bug?” The lone firefly’s fifteen minutes of fame lasts less than a nanosecond before it’s trapped between the tiny hands of a seven-year-old girl. Pamela is wearing a plaid skirt and a red sweater, the right sleeve trailing a kite’s tail of unraveled yarn. She’d caught the sleeve on his mailbox earlier that day when they were playing tag. She had started to cry, but he touched her arm, told her, “It’ll be okay.” She had smiled then, through her tears. He remembers that smile every time the sun comes out while it’s still raining.

He wishes it were easier to rewind the film. He would watch this scene a hundred times. But reversing the film stresses the brittle, precious celluloid. He has spliced all the two-and-a-half-minute films he owns into a single reel. It is the biggest reel he can fit on his ancient and miraculous Bell and Howell movie projector, and the most film that the take-up reel can hold.

“I’m sorry about the way the camera jiggles,” he says to Miranda. “We didn’t have image stabilization back then. We just had hands. And my mother’s hands wobbled a bit.”

The image shifts to a birthday party. A pirate party. This is how he knows it’s his tenth. But he isn’t watching the picture of the boys and girls stabbing at chocolate cake or mugging for the camera. He’s picturing his mother’s hands. Hands that shook nearly all the time, except when they were making bread. Her fingers seemed at home kneading, then punching the sticky dough, the way a kitten seems at home when snuggled in the smallest of spaces. He can smell the yeast, feel the tickle in his nose as the flour dusting the air dares him to sneeze. He turns away as if the sneeze is real, but despite the mites he can see dancing in the projected light, it is not. He returns his gaze to the screen.

The image flickers again across another splice, and they are looking out a car window at a shaky view of tress blurring by. A family vacation.

“We had an AMC Matador, brown,” he says to Miranda, who remains silent. “A station wagon. Ugly car by all measures,” he says, “except one. It was the family car. The family car is never ugly.” He knows this isn’t true for some. He has heard their childhood horror stories. But it is a truth he will always hold onto with both hands, the same way he is holding onto the railing at the Grand Canyon that is now appearing on the screen.

“The wind was really strong,” he recalls. “I mean, it was howling.” He nods toward the shadow of Miranda. He imagines her nodding back, trying to recall a similar sound in her own story. Her eyes would glance toward the ceiling as she searched for a memory of an insistent wind. He wonders if her memory would be a friendly ghost, or the menacing kind. He leans backward slightly, feeling an echo of the vertigo the wind had brought him that afternoon.

Howling wind is not the sound he hates the most.

The next scene is out of order. He means to fix that, but it’s hard to find splicing supplies these days. It is a misty autumn morning and he is five years old. The camera is steady.

My father’s hands.

He is as tall as the tiny elm tree that years later would tower over his childhood home, dropping leaves so earnestly onto neighbor’s yard that she filed a formal complaint with the city. The complaint was appropriately ignored by city council members for months, but by the time they had finally formulated a response (“the tree can stay – the leaves aren’t doing this to annoy you – buy a rake”), elm disease had already determined its fate. It was cut down in its twenty-third year.

He is wearing a Halloween costume, waving to the camera. There is always waving. It is a Batman costume. A gray one, inspired by the campy TV series he loves. Homemade, by his mother’s shaking hands. His brother, two years older and almost head taller, is wearing a companion Robin costume, also handmade.

“My brother wanted to be Batman,” he says. “But there can’t be two. So he acquiesced to my incessant whining. My older brother was a saint at seven. And until his last day…”

Maybe there could have been two.

“I’m sorry if this is boring you,” he says to the shadow of Miranda, but she doesn’t complain.

He looks back at the screen and begins to feel the beat of his heart against his chest. There, with a full head of hair and a wide smile that could end wars, is his father. He is older now than his father was in this scene. By decades. This is a strange and difficult thought to hold for long, so he lets it go.

“This is me at thirteen,” he says. “I was not the most pleasant teenager in the world, but then, who is?”

His father is ruffling his long hair and he’s grimacing and pulling away, wearing the time-tested expression of an exasperated teen. His father reaches around his shoulder and pulls him into a reluctant side hug. The “leave me alone” pout softens just a little before he pushes his father away and disappears off camera. His father shrugs, picks up a football, points across the yard, and mouths “Go long!” The scene ends.

Hi Dad.

There are two more short films spliced onto the end of the reel.

“I probably should explain this,” he says, nodding at the model spaceship jerking across the screen in stop-motion animation. “When I was sixteen, I decided I would be a filmmaker. This,” he points to the cigar-shaped ship he had cobbled together from three different models – a rocket, a hot rod, and a jet – that is clearly suspended by thread against a poorly-painted backdrop of space, “was my Star Wars.”

He laughs.

The image changes again.

“And this?” He watches a paperclip unbend itself on his old kitchen table, then wriggle slowly across the surface like a mechanical snake. Periodically, there is a glimpse of his fingers in the frame. “This is my audition tape for Pixar.” He laughs again. “I know, I know. Pixar wasn’t a thing back then. You’ll have to allow me one out-of-context reference here. Just one.”

He looks over to Miranda. Sighs.

There is no Miranda. Of course there is no Miranda. He is alone. He is not quite so crazy as to think she is really there, but he is nevertheless grateful for the shadows that suggest she could have been. Miranda is not her real name. It is merely the name he has chosen this time. He cannot use her real name because it is so gentle and powerful and perfect on his lips that to speak it wounds him.

The paperclip has bent itself back into its original shape.

He tenses, knowing what comes next.

The 8mm film is dragged, snakelike, through the twisting path in the projector until the screen goes white. The take-up reel does what it has been created to do and spins it around and around, unmoved by the sound that breaks his heart.

Flap, flap, flap, flap…

This is the sound he hates most: The sound the end of a thing makes.

He doesn’t turn off the projector. Instead, he turns toward Miranda to try to explain it. But there is no Miranda. And there are no words.

He reaches over to feel the heat emanating from the projector’s hard-working motor. The charged air smells like another memory. One for which there is no filmic record.

…flap, flap, flap…

It is Christmas morning and he is seated on the carpeted floor of his living room. A train is traveling around an oval track. He turns the dial to Forward, then Stop, then Forward again. It is a train he had wanted for so long he memorized every detail about it from the Christmas catalog where he’d double-dog-eared the page and carefully circled the description in red. And here it was, exactly as promised.

It is perfect. It is beautiful. He feels joy. True, unbridled joy as the train obeys his every command. As it runs around, and around, and around the track.

He feels something else, too. Something like an ache. But he has no words.

…flap, flap, flap…

He turns off the projector.

…flap…flap…

…flap.

2 Comments

jules

The sound of loneliness…

Jenny the bloggesss

“This is the sound he hates most: The sound the end of a thing makes.” I could write all week and not create anything as perfect as this.